By John Zangas

By the banks of the Dan River near Eden, NC, there is a sign that says, “This is your drinking water… help keep it clean!”

Apparently Duke Energy didn’t pay attention to it.

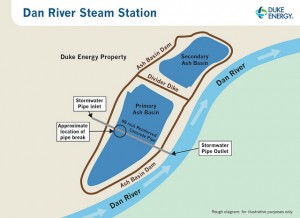

On February 2, toxic coal ash leaked into the Dan River from a pit at the Duke Energy power plant in Eden, NC, which has been closed since 2012. Within hours, up to 82,000 tons of coal ash combined with toxic metals and contaminants flowed downstream.

It was over 24 hours before Duke Energy reported the leak. Four days later, Duke Energy claimed it had contained the spill, but Waterkeeper Alliance, a river watchdog group, reported on February 13, almost two weeks later, that pollutants were continuing to leak into the river. A thick layer of coal ash residue still extends along river banks and deep into the water a mile downstream.

The Dan River is an important water source for the region. It flows for 200 miles, criss-crossing state lines six times between North Carolina and Virginia. The 200 million year-old river nourishes forests and farmland and provides potable water to scores of towns and cities, including the city of Danville, Virginia–only twenty miles downstream from the site of the coal ash spill–with a population of 43,000.

The Dan River is an important water source for the region. It flows for 200 miles, criss-crossing state lines six times between North Carolina and Virginia. The 200 million year-old river nourishes forests and farmland and provides potable water to scores of towns and cities, including the city of Danville, Virginia–only twenty miles downstream from the site of the coal ash spill–with a population of 43,000.

Danville water utilities reported that water samples submitted to a private lab showed water at its purification plant are within standards. Duke Energy also says that tests taken four days after the spill showed water was safe to consume.

But Duke Energy and the Danville Utility’s testing methods are being called into question. If the testing is not accurate, they may not be right about whether the water is safe to drink and use.

In one instance, an independent test conducted by Waterkeeper Alliance reported levels of arsenic ten times over the safety limit, contradicting Duke Energy’s claims that levels of arsenic were within safety guidelines.

Another scientist, Scott Smith from environmental organization Water Defense, disputes how Duke Energy and the Danville Utility are arriving at their results. He was at the Dan River a week after the spill, taking samples and running an independent test for toxins. The future of the river is in doubt, he said.

Smith has previously conducted independent testing at disaster sites. “The metals in coal ash can include selenium, mercury, arsenic and lead and a variety of other metals that are dangerous,” he said. These toxic metals can accumulate in river life over time and get passed up the food chain. They poison the water, affecting aquatic life and animals such as livestock which depend on the river.

Smith has strong feelings both about the testing procedures and method being used by officials to test the Dan River. “There is no transparency,” he said, “The state of North Carolina is doing testing but they’re not revealing their protocols or where they’re testing.” He also criticizes their test methodology. Duke Energy, the N.C. Department of Environment and Natural Resources and the Danville Utility are using the same type of water testing called spot sampling.

Spot sampling is a discrete grab of water from a particular location, basically dunking a bucket into the water and drawing it up. Duke Energy and the Danville Utility won’t reveal where they are taking their samples, according to Smith.

Smith invented a new water testing technology which uses “accumulated sampling method.” He believes that it is more rigorous than spot sampling. Water Defense organization used the same technology to measure the toxicity levels in the Gulf after the Deepwater Horizon Platform oil spill of 2010.

He places green sponge-like material into water, shaped like rows of giant combs, to attract impurities in the water over a period of time. He deployed it a mile from the Dan River coal ash spill site to test for toxins.

He says that Duke’s method is inadequate because collecting water samples at split-second intervals would not measure toxins that build up in aquatic river life over time.

“Instantaneous water sampling is not the basis to test,” he said. “Accumulated water testing is much more thorough and indicative of what is in the water.”

“If you’re a fish or a kid swimming in the water in the summertime, you want to know what you are exposed to over that period,” he added.

Furthermore, he worried that tests were not being conducted for other types of non-metallic carcinogens, known as semi-volatiles, which exist in coal ash pits. “These can be just as dangerous as the metals in the water,” he said. Duke is only reporting levels of metallic toxins, not semi-volatiles.

“All this stuff is being introduced into the river in an unprecedented way,” Smith said. He’s worried about the prognosis for the river. “The concern with this spill from what I’ve seen so far is not only is it going downriver, but these heavy metals clearly sink to the bottom and banks of the river,” he said. “I don’t know how you clean it up.”

Smith said that his test results, unlike Duke Energy’s, will be comprehensive. He expects them to be completed within several days.

Meanwhile Danville and other downriver communities continue to drink and use water supplied from the Dan River.

“I wouldn’t wash with or touch it,” Smith said.

(DMCG will update this article when Water Defense releases its test results.)

Interview with Scott Smith, chief scientist with Water Defense: