In Cecily McMillan’s arrest in Zuccotti park, the New York prosecutor’s office found an outlet for its fury at Occupy Wall Street. The District Attorney seized the opportunity and held onto it like a dog with a bone.

It would be the height of absurdity to charge with assault a woman who defended herself from sexual assault–yet this is exactly what happened. During one of the most egregious NYPD crackdowns on Occupy in March 2012, someone grabbed Cecily McMillan from behind on her right breast. She elbowed the assailant. It turned out to be a plainclothes police officer. On May 5, 2014, more than two years later, a kangaroo court convicted her of felony assault in the second degree and sentenced her to ninety days in prison.

McMillan was the stand-in for every Occupy Wall Street protestor who had escaped jail time. For almost all others, the charges didn’t stick, or they took a plea bargain. New York had to pay out hundreds of thousands of dollars for police abuses, including one settlement made this month for $583,000 for alleged wrongful arrests.

Mostly, McMillan’s prosecution was a warning shot to other dissenters: look at what will happen to you if you step out of line.

Sixty Days in Rikers

After fifty-seven days at Rikers Island, New York’s main jail complex, Cecily McMillan can’t hold back a torrent of words. About privilege, activism, the injustices she’s seen. She heaps praise on her fellow inmates. She can’t say enough about them.

I have been challenged like I have never been challenged before as a nonviolent activist to really keep it together here, to not use verbal or physical abuse. I will not say that I could have done it on my own. These women have kept me alive in here, sustained me.

She’ll be released in a few days, on July 2, after serving sixty days of a ninety-day sentence–thirty days cut off for good behavior. She still isn’t scot-free. She has five years’ probation. More worrisome, she has another trial coming up on July 17 for allegedly interfering with an arrest of two teenagers who jumped the turnstile in a subway station. She isn’t allowed to talk about the case.

For now, I can tell that she’s wholly immersed in daily life in Rikers and in the lives of the women she’s with.

“Heartbreak today,” said the update posted last Thursday on her website. Jack, a friend and dorm-mate, died of Hepatitis C and undiagnosed cancer after three days of coughing up blood. Delirious, Jack had resisted medical treatment.

It was an entire dorm-wide effort to watch over [Jack] for days trying to get her to go down [the stairs]… as she slipped into delirium before she went into the final stages. When they didn’t take her or send up a stretcher, we—all of us—kept her up, kept her awake, kept her lucid. Two or three girls fought with the guard to be able to walk her down.

Also last week, one of her close friends, Fat Baby, fell in the shower and hit her head. She woke the following morning and couldn’t move. Staff refused to let her see a doctor, so with help Fat Baby submitted a grievance. A grievance form was returned to her filled out by someone else, and she was told to sign it. McMillan thinks they misplaced the original. Fat Baby refused to sign.

I spoke to McMillan on the phone in fifteen minute increments. (Each time we re-connected, she immediately took up where she left off.) I had heard plenty about the for-profit Prison Industrial Complex phone scam, which bleeds inmates and their families dry. Twenty-five dollars buys twenty-one minutes of conversation, I discover. In the background, voices rise and fall, doors slam.

“Every woman has been on the phone every day like I have been, trying to organize their families, managing to live through this hellhole,” she says. I forget to ask how they manage to scrape together the money to pay for it. Undoubtedly, there is a debt scam to underwrite the phone scam.

McMillan’s time in Rikers may have taken a toll, but it has not broken her. She describes the many indignities there as struggles endured in solidarity with comrades, not as personal complaints. She says that before Rikers, she didn’t know that placing your hands on your hips expressed defiance. In Rikers, she says, you have to keep your head down, your hands behind your back–postures of compliance, passivity. She sleeps in a dorm room with forty other women. There are invasive searches of your personal items, your body. Her phone calls are recorded. Contrary to the notion of inmates lazing about watching the clock tick, prison is endless activity, endless lines. It’s the movie Brazil “on steroids,” she says.

Still, her mind isn’t dulled, nor her spirit crushed. She is thinking, writing, planning, talking.

Letting Others Lead the Way

She wants to talk activism. I’m overjoyed. Activists can’t help hashing over the questions which obsess us. How do we bring about the change we want to see in the world? What strategies are effective? How do we live? What more can we do? Maybe because she’s talking to someone else who was infected and changed by the Occupy movement, her words flow unfiltered, infused with energy and enthusiasm.

I forgot in my organizing community what it meant to be both a human being and an organizer. When you lose sight of the fact that you’re a human being, how to talk to people, how to laugh with people, how to engage in recreation or a meal with somebody, you’re not able to be a good organizer. I think you lose humanness. It should be the foundation of everything that you’re doing.

Her activism rests on this humanism and the recognition of privilege, that certain groups of people enjoy inherent advantages and immunities by virtue of, for example, race and class.

I don’t need to teach anybody or provide anybody with some sort of organizing. The poor, people of color, anybody who is oppressed in living in this country is an organizer. You have to be an organizer to some degree to survive here against all odds of oppression–to fight to live, to breathe. Without healthcare, without resources. So when I came in here I sat, I listened and I waited and I tried to be of help. I didn’t try to organize anyone or anything. I was here and present and available.

She distinguishes herself—half-Hispanic but passing as white, college-educated, with outside support—from the women she’s incarcerated with, for whom it’s “not if, but when” they go to Rikers.

When you give them the resources to do something, they are above and beyond capable, beyond anybody, most people that I have seen that have come from a privileged background, because they know how to be resourceful. And when they don’t have the resources, they make them, or they take them. And that’s why most people are here, point-blank.

Few would consider McMillan to have come from privilege herself. She grew up in rural Texas, and her parents divorced when she was young. Both her mother, an immigrant from Mexico, and her father of Irish descent struggled to find decent work. They relied on welfare during stretches of unemployment.

I have brothers in prison for being a drug dealer, for being a meth addict. I come from trailer parks, and most of my friends are three or four kids deep and having to do questionable things to keep alive. And there were many times I was homeless, hungry. I slept various places, should have gotten killed. But somewhere along the way, I think I worked my way up the ladder.

Even so, she regards herself as comparatively privileged with the support and attention she has received from publicity about her case. (Although, as Molly Crabapple points out, she may have received more attention as a political prisoner abroad than at home.) She told Chris Hedges:

People of color, people who are poor, the people where I come from, do not have a chance for justice. Those people have no choice but to plea out. They can never win in court. I can fight it. This makes me a very privileged person.

She believes that the more privilege you have, the more you should step back and let those with less advantage lead the way:

It’s not really for you to determine what the problem is and what needs to be fixed. That’s not your role. It’s your job to be there and to provide help if asked.

In that respect, Occupy Wall Street got it wrong.

Occupy Wall Street was great taking that first step. But the problem is that they said, “Hey, we’re the 90-99%, all the rest of you Zero-to-Ninety, come to us. We have the solution, and we’ll tell you how to do it.”

Anybody who is standing there with a Columbia Ph.D. and practically living off their trust fund is, you know, they’re claiming revolutionary as they’re downwardly mobile, wearing uniglo and all black. Like folks screaming “Fuck the police!” You know you’d fucking call the police if you got held up by gun point. You have no idea what police repression is. You have no concept of what want is, what need is, what not just if but when I’m going to Rikers is. It’s not up to you, who has struggled little comparatively, to decide for the masses.

Those Left Behind

“Yo, activist! They’re fucking with our free time. What are you gonna do about it?”

Rikers staff had been scheduling meals, medication, mail distribution and recreation all at the same time. It led to a “dorm collective action.” Petitions aren’t allowed (somehow they are construed as attempts to incite a riot), so they waged a “grievance campaign” —each submitting identical grievances. It was successful.

If it hadn’t been, McMillan probably wouldn’t have been shy about turning to the media to put on some pressure. She fully realizes that her high-profile case has given her a platform and window of opportunity, and she intends to use it.

“I’m going to make sure the voices of the folks in here that are systematically shut down, silenced–even shot down—can be heard,” she says.

After she deals with the charges of interfering with an arrest, the twenty-five year-old is leaving New York. She wants to go to Atlanta and start a collective house for activists, inspired by settlement houses like Jane Addam’s Hull House in Chicago.

In talking with me, she’s made little reference to the traumatic attack at Zuccotti, the unjust charges, or the long, stressful period between her arrest and trial. The present at Rikers seems all-consuming. She reflects on the effect that prison has had on her:

If this has changed me at all, it has humbled me. When I came home from college my first year, my grandmother said, “Ceci, I can’t understand a damn word you’re saying.” [Falls into Southern accent] “You’ve gone and got above your race.” [Laughs] And I was like, “What the fuck?” And it’s true, I had. I’d forgotten I don’t have all the answers. I forgot that to talk to people you need to meet them where they are. To help people, you need to listen to their problems. I didn’t know that violence can be so institutionalized that people are literally socialized from birth with the physicality of powerlessness.

“It’s gonna be very hard for me to walk out of here without them,” she says of her friends in Rikers. “And I think there is a way that I’m gonna be able to talk about struggle now that is a lot more real, that is a lot more shared.”

She suggests that she might not–ought not–leave Rikers when her time is up, as a protest against prison conditions. I hear guilt in her voice about having something more—at least intangibly–than those she’s leaving behind. She knows that the press will be waiting for her to appear at the gates, people who love her will be waiting to embrace her. She will have the freedom, inspiration and energy to pursue a vision. Unlike many, she has a priceless gift–a future with promise.

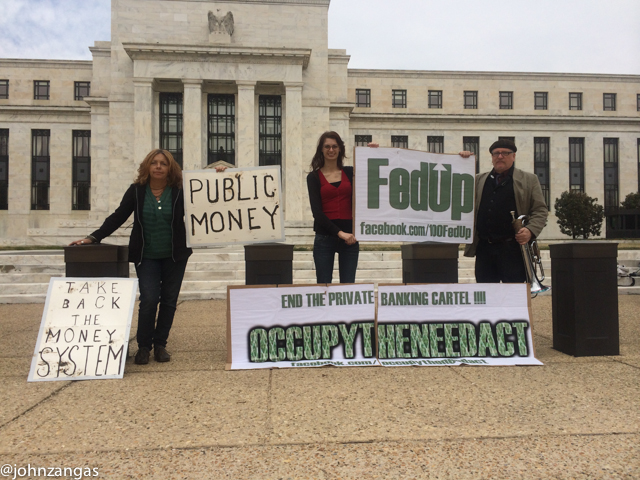

John Zangas contributed to this article.