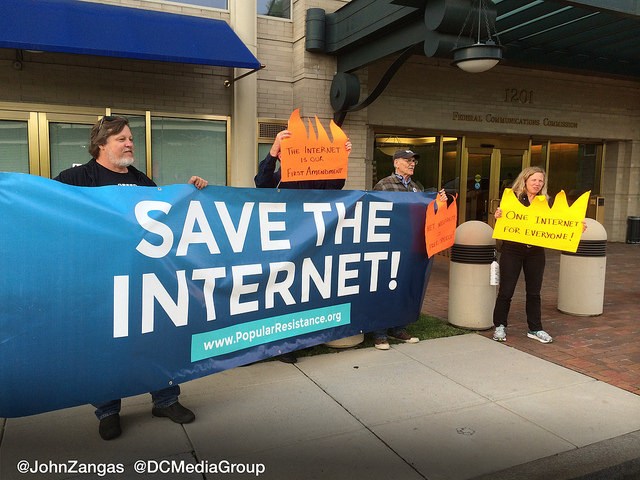

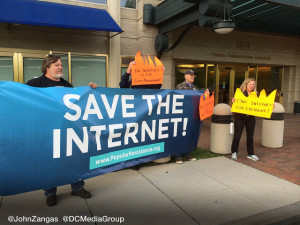

The “Save the Internet” fight waged against telecoms for Net Neutrality was an epic David vs. Goliath battle. Grassroots Net activists with little funding and handmade signs were pitted against deep-pocket telecom Titans and legions of lobbyists skilled at smoothing Congressional corridors. Ultimately, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) debated and voted for an open and free Internet on February 26.

The “Save the Internet” fight waged against telecoms for Net Neutrality was an epic David vs. Goliath battle. Grassroots Net activists with little funding and handmade signs were pitted against deep-pocket telecom Titans and legions of lobbyists skilled at smoothing Congressional corridors. Ultimately, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) debated and voted for an open and free Internet on February 26.

Although the movement for Net Neutrality had been simmering for several years, the public had to become educated on a wonky subject and mobilized quickly and effectively. The goal was regulating the Internet as a common carrier under Title II of the Telecommunications Act.

Yet the battle for the Internet was lost almost before it began. In May 2014, the FCC was poised to cede the Internet to the Big Telecoms–AT&T, Comcast, Verizon and Time-Warner. Marvin Ammori, an attorney on the Board of Fight For the Future (FFTF), knew they were facing difficult odds. “It looked unlikely we could ever win,” he said. “We had to move mountain after mountain.”

And they did move mountains, including Congress and the regulatory bureaucracy in thrall to the big Telecoms.

Many worked to make it happen. Exactly how did they do it? Does this victory represent a new landscape for grassroots organizing? And is this a new model other movements can follow in going up against the Corporatocracy?

What’s At Stake

With Net Neutrality, ideally everyone is guaranteed equal access to information via the Internet at equal speeds. Although the Internet originally was set up with equal access, the FCC was on the verge of permitting Telecoms to convert it to a tiered system favoring priority users.

At stake was everything we think do and say on our cell phones, computers, web pages and wi-fi devices. Everyone from librarians to doctors and non-profits to businesses would be affected by preferential treatment given to those who could pay more.

“For smaller companies, it was a life or death situation,” said Ammori of FFTF.

“Ensuring the future of the Internet was an issue that should unite every advocacy group because it impacts each of us,” said Kevin Zeese of Popular Resistance. “If the Internet had become a tiered service, our ability to exercise our Freedom of Speech would have been severely undermined.”

Building A Coalition

Craig Aaron, President of Free Press, has been working for Net Neutrality since 2005. A Supreme Court decision that gave cable companies exclusive rights (the “Brand X” decision) alerted him to the potential loss of public Internet access.

Craig Aaron, President of Free Press, has been working for Net Neutrality since 2005. A Supreme Court decision that gave cable companies exclusive rights (the “Brand X” decision) alerted him to the potential loss of public Internet access.

Free Press began building a broad coalition of groups to petition the FCC for Title II reclassification under a campaign called “Save the Internet.” Aaron was quick to give props to more than another 40 groups, such as Demand Progress, Popular Resistance, Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) and Fight For The Future (FFTF). “We kept plugging away at Net Neutrality and filed hundreds of pages of detailed comments with the FCC,” he said.

Ammori said that the groups weren’t talking directly to each other so the key was to coordinate them. He focused on pulling together start-ups in the business community.

Malkia Cyril, Director at Center for Media Justice (CMJ), a media watch group which co-founded the Media Action Grassroots Network (MAG-Net), a national broad base network of 175 community organizations, organized them to “help overcome opposition attempts to use race as a wedge in the fight for Title II Net Neutrality”. CMJ and MAG-Net organized the most underrepresented communities into a national movement for media rights, access, and representation. “Together, we secured 100 civil rights endorsements for Title II, tripled the number of Tri-Caucus members in support of Net Neutrality,” Cyril said. Key achievements included persuading the Congressional Progressive Caucus to endorse Title II. Caucus members like Reps. Barbara Lee, John Lewis, and Keith Ellison issued public statements in support of it. A broad political reach under her stewardship gave the movement clout.

For social justice action groups, Kevin Zeese, co-founder of Popular Resistance, was one of many key players in coordinating activists and on-the-street actions. His strategy was to stay in the FCC’s field of vision and keep the pressure on.

Grassroots Tactics For An Open Internet

In early May 2014, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler’s proposal for a tiered Internet leaked. The week before the public meeting scheduled for May 15, Zeese and a dozen supporters erected several tents on the small patch of grass at FCC headquarters and called it “Occupy the FCC.” By the end of the week, there were 20 tents with signs and banners and scores of Net activists camping out.

In early May 2014, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler’s proposal for a tiered Internet leaked. The week before the public meeting scheduled for May 15, Zeese and a dozen supporters erected several tents on the small patch of grass at FCC headquarters and called it “Occupy the FCC.” By the end of the week, there were 20 tents with signs and banners and scores of Net activists camping out.

The Occupation had a major effect. “TIME Magazine reported that the FCC was in a panic,” said Zeese. Occupy the FCC caused social media to flood with photos of tents, signs, banners and Internet activists staking out the FCC.

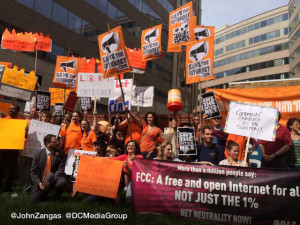

Hundreds joined them on May 15, the day of the Commission meeting. Chairman Wheeler bowed to pressure and included language with an option to include Net Neutrality language. He also initiated a public comment period for 120 days.

“Once that door was open the movement came through it aggressively,” said Zeese.

John Oliver’s Epic Viral Video

On June 1, 2014 John Oliver took on the issue of Net Neutrality on his show Last Week Tonight, when he compared putting former telecom exec Tom Wheeler in charge of the FCC to a placing your baby in the care of a dingo. His follow-up epic 13-minute skit was a call to arms for Internet “trolls.” Saying that this was their moment to shine, he directed them to the FCC comments site.

On June 1, 2014 John Oliver took on the issue of Net Neutrality on his show Last Week Tonight, when he compared putting former telecom exec Tom Wheeler in charge of the FCC to a placing your baby in the care of a dingo. His follow-up epic 13-minute skit was a call to arms for Internet “trolls.” Saying that this was their moment to shine, he directed them to the FCC comments site.

“Turn on caps lock and fly! Fly, my pretties, fly!” Oliver exclaimed, borrowing a line from The Wizard of Oz.

The next day, FCC servers and phones crashed as 45,000 overloaded its capacity with their comments.

Most who worked on Net Neutrality described John Oliver’s show as a seminal moment. “As someone who has been trying to message this issue for ten years, you watch John Oliver for ten minutes and say ‘Oh! That’s why he does what he does,'” said Aaron. But he also credits Net activism for creating the space for Oliver’s video to go viral. “Before that video there were already a million people who had commented,” he said.

Tech Companies Try Activism

On September 10, web companies such as Reddit, Vimeo, Kickstarter, and Mozilla voluntarily slowed down traffic to their websites to demonstrate how business could be affected without Net Neutrality. The result was delayed service, slow downloads and user frustration as the public began to understand an outcome of tiered Internet service.

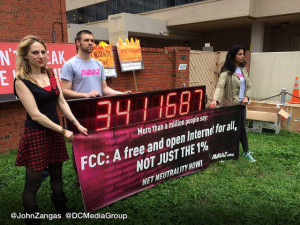

On September 15, the day before the FCC public comments period ended, Fight For the Future partnered with Namecheap to erect a giant electronic billboard in front of the FCC. Anyone could submit homemade videos to tell the FCC why the Internet should remain open and free. This gave the public an opportunity to speak directly to the FCC, right outside its door. By the deadline, the FCC had received 3.4 million comments and their served crashed again, and there were too many phone calls for the FCC to answer.

The next morning, as the hearing convened, the coalition of dozens of Net groups protested outside, while inside, Net activists disrupted the meeting and were ejected. A protest of this size and scope was unprecedented at the FCC, an obscure agency tucked among grey government buildings.

Off The Computers, Into The Streets

Zeese of Popular Resistance borrowed from Howard Zinn’s advise for social movements: go where you are not supposed to go, say what you are not supposed to say and refuse to leave when they tell you to go. “In the net neutrality battle that meant going into their public meetings, interrupting and hanging banners in the meeting rooms,” he said.

Zeese and several other activists interrupted meeting after meeting, and were thrown out of the FCC several times. They also pranked Chairman Wheeler in his driveway, blocking him from leaving for work with a banner while singing a parody to Guthrie’s “Which Side Are You On,” tacking on “Tom” to the end. They uploaded the video onto YouTube. They also staged a tug-of-war game with rope and Net activists tugging against faux FCC commissioners outside the FCC. With each event ,they drew arcane concepts of Net Neutrality closer to the mainstream.

Obama finally came out in support of Net Neutrality on November 10, urging the FCC to adopt strong language preserving an open Internet under Title II. But most of the work had been done turning popular opinion, according to Ammori. “By that point we had gotten dozens of Senators and Congressmen on our side,” he said. He also attributed Free Press with “building support one ally at a time, one activist group at a time-it all just built up.”

“Nothing Is Impossible”

By December 2014, Evan Greer, Campaign Director of Fight For The Future, and her seven team members were seeing for the first time that victory was finally possible but funds were running low. With the end of the battle in sight, Greer wrote to members, “We’re up against some of the most powerful and politically well-connected companies in the world, [and] the closer we get to winning a real net neutrality rule, the more desperate and aggressive Comcast and Verizon’s lobbyists become.” Greer asked the 1.2 million members to contribute whatever they could afford, even if it was a dollar, but even if they could not contribute, to be encouraged for being a part of the movement that was winning.

Fight for the Future staff built website tools to make submitting comments to the FCC easier. They devised a shortcut to bypass the phone switchboard and reach the desks of FCC personnel directly. Being able to unwrap the insulation between the public and telecom lobbying power at the FCC was key to causing disruption.

By the end of the comment period nearly 4 million had responded to the FCC, according to Zeese.

On January 7 of this year, FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler spoke publicly for the first time in support of Net Neutrality, saying, “We’re going to propose rules that say that no blocking, no throttling, [no] paid prioritization, all that list of issues, and that there is a yardstick against which behavior should be measured.”

This was the moment Net Neutrality supporters had been waiting for. The key vote in the battle was yet to come, but by February, they would know for sure. On February 4, Wheeler wrote an article published in Wired Magazine. “I am proposing that the FCC use its Title II authority to implement and enforce open internet protections,” he wrote.

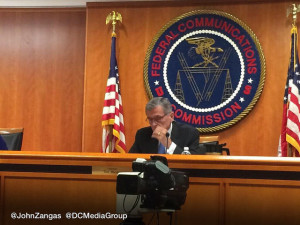

Key FCC Vote

The Commission vote on February 26 was 3-2 in favor of Net Neutrality and resulted in victory after nearly a decade long fight. The FCC finally ruled that the Internet will be designated a Public Utility under Title II. It means access to it and use of it will be equal for everyone, no matter what Internet service provider they use or which data plan they choose. It also means the Telecoms can’t control and rule over the Internet as if it were their corporate property.

Congressman Grayson, whose office helped set up the website www.fccDoYourJob.com to facilitate public comments to the FCC, described the FCC vote as a key moment in communications history. “It fulfills the promise of the virtue of organizing [as] we’ve had

some disappointing experiences trying to organize mass movements,” he said. “But every once in a while we break through. This is one of those moments.”

A Blueprint For Movements

“A new political force has shown its power. The community of Internet users is able to mobilize effectively,” said Zeese. He believes in the power of the people and that corporate interests should not underestimate it. If people work in solidarity toward a common objective, they can overcome anything, “as with every issue in this country the power of big business in the US plutocracy.” He said key advantages in this movement were coordinated efforts sustained over many years, building group cooperation, and refusal to compromise or go back on its goal, which would have opened the movement to failure. A watered down version of Net Neutrality would have eventually lead to failure.

Other movements can take notes for success from the Internet community. Forming coalitions, finding key people who coordinate behind the scenes, not being afraid to take direct action to apply pressure, and refusing to settle for anything less than the goal, were all key components to winning the battle for the Internet.

Each movement is different, however. “Once you share a common goal and a broad strategic outline, respect the tactics of coalition partners as it takes a variety of tactics to achieve the goal,” said Zeese.

The Future for Net Neutrality

Open and equal access to electronic communications on the internet is likely to be revisited with evolution of communication technology. But as long as Title II of the Telecommunications Act of 1934 remains in place, it’s guiding principles will keep the Internet open and free.

Open and equal access to electronic communications on the internet is likely to be revisited with evolution of communication technology. But as long as Title II of the Telecommunications Act of 1934 remains in place, it’s guiding principles will keep the Internet open and free.

The people will have to remain vigilant for challenges to Net Neutrality from Telecoms. New technologies which may result in unforeseen changes to the Internet may require new laws of governance.

Aaron believes Telecoms will file lawsuits against the FCC, and challenges from the Republican-led Congress will cause the issue to come up again. But many groups will keep up with them. “We’ll be involved in intervening in those lawsuits,” he said. “We think we get much better policy when the public is involved.”

Vigilance will need to be generational, Ammori believes. “There are ways to undo it,” he said. “We have to make sure that it such an overwhelmingly popular thing that if the FCC tries to undo it, Americans will erupt in anger.”

Until then, Net Neutrality activists can savor their hard-earned victory. They stood up to Titans and won.