Facing long odds, residents of southwest and central Virginia remain confident their organizing efforts will lead to victories over pipeline companies that want to seize their land through eminent domain to build major natural gas transmission lines.

Facing long odds, residents of southwest and central Virginia remain confident their organizing efforts will lead to victories over pipeline companies that want to seize their land through eminent domain to build major natural gas transmission lines.

Virginia has a reputation as a business-friendly state where politicians do the bidding of major corporate players with little resistance from its citizenry. But residents who live along proposed pipeline routes have grown tired of their voices being ignored.

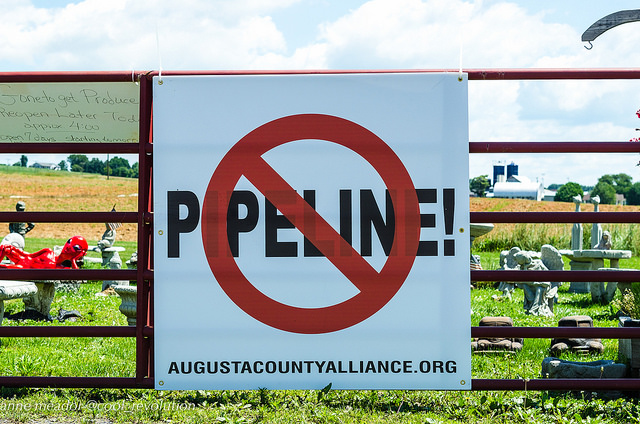

Through groups like Friends of Nelson County and Preserve Montgomery County, Va., residents in these mostly rural areas of Virginia have united against the proposed energy infrastructure projects. The timing of the residents’ campaign—in the wake of a series of anti-pipeline victories in other states—combined with their determination could be a potential recipe for success.

The anti-Keystone XL Pipeline movement in late 2015 finally succeeded in stopping construction of the northern leg of the diluted bitumen pipeline in the Great Plains states. Campaigners in New York State successfully pressured state regulators earlier this year to deny a necessary permit to the developers of the Constitution Pipeline. Kinder Morgan Inc. also recently suspended development of its controversial Northeast Energy Direct gas pipeline project in New England.

Virginia does not have the same tradition of anti-corporate or social justice activism found in New York, California and other states. But the decision by pipeline companies to move forward with their projects in the face of widespread opposition spurred Virginia residents to take a stand. Carolyn Reilly, a former sales and marketing representative, lives on a 50-acre farm in Franklin County, Va., a portion of which the developers of the Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) want to obtain through eminent domain.

“This is our time to rise up and speak for what matters,” Reilly, an organizer with the Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League (BREDL), said in an interview. “We’ve been inspired by New York. These other pipelines were stopped or delayed because of communities banding together and saying, ‘No, we’re not going to take this.'”

The resistance to the MVP and Dominion Resources Inc.’s proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP), which would cross into Virginia from West Virginia north of the MVP, closely mirrors efforts in Pennsylvania against Williams Cos. Inc.’s proposed Atlantic Sunrise pipeline. In Lancaster County, Pa., for example, residents have built a strong opposition group that is fighting Atlantic Sunrise using both environmental concerns and private property rights as weapons. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency recently chimed in, urging the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to take a closer at alternatives to Atlantic Sunrise. One of the EPA’s alternatives would ultimately negate the need for the Atlantic Sunrise project.

In Virginia, groups are pushing regulators and pipeline developers to reconsider the construction of the MVP, the ACP and other gas pipeline expansion projects. “We would like to see Dominion take a step back and reconsider the need for [the ACP], rather than continuing to blindly push forward a destructive proposal in the face of tremendous community opposition,” Southern Environmental Law Center Senior Attorney Greg Buppert said in a recent statement.

The idea that a natural gas pipeline company could confiscate Reilly’s property through eminent domain opened her eyes to the immense power that corporations hold. “This campaign has given me the ability to raise my voice against something that is not right for landowners and rural people who are being bamboozled with proposals of lots of money,” said Reilly, who lives on the farm with her husband and four children.

Virginia has a business-friendly reputation, but its residents also embrace private property rights, noted David Sligh, a former senior engineer with the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. “When you have a situation where private companies can take your land for their own purposes, we don’t believe that conforms to how America is supposed to work,” Sligh said in an interview.

For both the MVP and ACP projects, Virginia’s environmental regulators should follow the lead of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation in its refusal to grant Constitution Pipeline’s request for a water quality certification under the Clean Water Act, asserted Sligh, who now serves as an investigator for the Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition and works as an environmental attorney.

“That’s the reason the Constitution Pipeline stopped in New York: because the state agency said, ‘You have not proved to us that you’re not going to mess up our water quality.’ We don’t believe they can prove that here. We don’t believe they can prove that cutting across these mountains and through these valleys won’t mess up our water resources,” he said.

March on Richmond

Reilly plans to join fellow Virginians at a July 23 event in Richmond dubbed March on the Mansion. According to the event’s organizers, Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a Democrat, refuses to listen to their calls for “solar panels, not pipelines, clean water, not coal ash, and real democracy, not polluter politics.” Among the march’s dozens of sponsors are the local anti-pipeline groups as well as the Chesapeake Climate Action Network, Appalachian Voices, 350.org and Bold Alliance.

In an open letter to McAuliffe, the march organizers explained they have asked the governor to reconsider “his blanket support” for the ACP and MVP projects and to use his legal authority to closely review and challenge water permits under the Clean Water Act. “We have warned him that these pipelines and the fracking wells they support could trigger nearly double the total greenhouse gas pollution currently emitted by all existing Virginia power plants combined,” they wrote. “But our voices have not been heard.”

If built, the ACP would be a 42-inch-diameter gas transmission system originating in Harrison County, W.Va., and running 550 miles into North Carolina. The pipeline’s capacity would be 1.5 billion cubic feet per day. The ACP would interconnect with the Transcontinental Gas Pipe Line system in Buckingham County, Va., allowing gas to flow north or south on the Transco system from there.

The MVP, a partnership led by EQT Corp., would transport about 2 billion cubic feet per day of natural gas produced in the Marcellus and Utica shale regions in northwestern West Virginia. The system would total about 294 miles, traveling south of Roanoke, Va., and interconnecting with the Transco system at a compressor station in Pittsylvania County, Va.

Fighting Back

In her work with BREDL, Reilly regularly speaks with residents who, like her, own property in the path of the proposed MVP route. “What I enjoy is meeting other people who are in my same shoes as a landowner or a farmer and the light bulb goes off: They have the right to speak up. They find their voice. That’s the gift of being an American, being able to speak out and take action to protect the communities we live in,” she said.

MVP surveyors showed up on Reilly’s property in May when she was giving a tour of her 50-acre farm to a group of school children. Reilly refused to allow the surveyors to conduct any work on her property. In response, the surveyors called the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office, who told Reilly that, under state law, she must allow the surveyors onto her property.

When a sheriff’s deputy arrived and informed her of the law, Reilly told him, “That’s too bad. They can’t be here right now.” The surveyors didn’t come back. “And we haven’t heard from them again,” she added.

In late June, FERC announced plans to issue a final environmental statement (EIS) for the MVP in March 2017. The issuance date for the final EIS would push back anticipated construction dates. The developers had hoped to begin construction in late 2016. “We celebrate the delay as a victory of sorts,” Reilly said. “If anything, it encouraged us to continue our efforts and to double them.”

Sligh predicts state authorities will change their minds and decide to take a closer look at the environmental impacts of both the MVP and ACP projects. In the end, he believes residents will succeed in defeating the projects.

“These folks are fighting for what they believe is their heritage, especially here in Virginia where people talk all the time about history and heritage,” Sligh said. “The natural resources are the most valuable thing to hang onto. People don’t intend to let it be destroyed easily.”