Ranson, W.Va.–Granny Smith Lane was until recently riddled with almost impassable potholes. If you navigated them successfully and wound your way to the end of the narrow, tree-lined roadway, you would reach a secluded corner of what used to be an apple orchard. Hardly noticeable, a few gravestones sit atop a small grassy knoll. More grave markers are jumbled among trees, vines and thorny bushes. Little effort has been made to clean up the trash strewn about or curb the groundhogs, who have constructed an elaborate burrow. A giant sinkhole warps the ground, and many graves are sunken depressions in the earth.

However small and untended, the burial ground in the Jefferson County, W.Va. does have a name—Boyd Carter Cemetery—and a long history. The original deed from 1902 says that the lot “is to be used for a burying ground for colored people and for no other purpose.” The first recorded burial was in 1904, and the most recent was in 1999. It harbors the resting places of several generations of African-Americans, some of whom were born enslaved. A local historian believes its history stretches back even further and originally, enslaved people may have been buried there.

While the cemetery may suffer from neglect, it is not forgotten. Descendants of those buried there do visit their loved ones and ancestors.

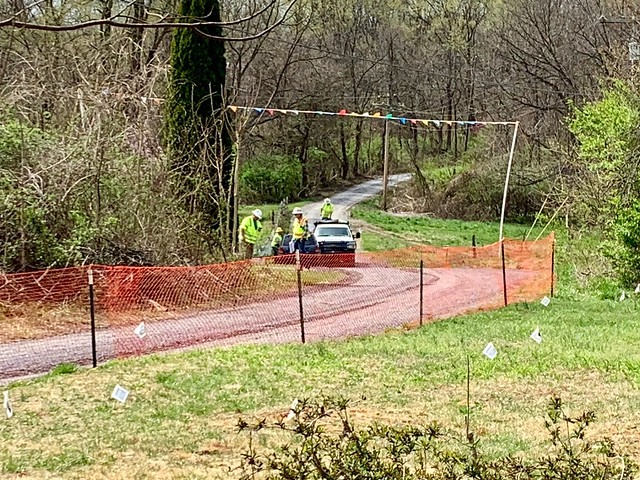

Up until this time, only tree roots, groundhogs and the shifting earth have encroached on the graves at Boyd Carter Cemetery, but now, trucks and heavy machinery rumble nearby. A trench digger approaches, only 100 yards away. The pipeline is coming.

Once an Orchard, Now a Factory

Boyd Carter Cemetery comes to attention now because it happens to border the site of the Rockwool mineral wool factory, now under construction. Mountaineer Gas was recently given the go-ahead to build the gas pipeline to service Rockwool. The company has plans to widen Granny Smith Lane, and the pipeline route passes within a few yards of the cemetery on two sides. The lane has been covered with gravel, and the verdant growth cut back. Heavy machinery snapped tree trunks like toothpicks and ground them to wood chips to clear the right-of-way.

The pipeline comes so close to the cemetery that the official limits-of-disturbance come right up to the cemetery boundary. Those boundaries are in dispute. Members of Jefferson County Vision who are working with descendants to preserve the cemetery have noted discrepancies in Mountaineer Gas’s maps from that in the original deed. They say the company has shrunk the area of the cemetery by as much as 60%.

An attorney representing descendants of those buried in the cemetery sent a letter both to Rockwool and Mountaineer Gas earlier this month warning them not to trespass. In addition, grave sites may be located beyond the boundaries of the cemetery, the letter says, and construction might disturb those remains.

Little white flags flutter where ground-penetrating radar found as many as ten unmarked graves, but these were only the ones with metal caskets. Those buried in shrouds or wooden caskets would not have been detected by radar. Some of the white flags line the edge of the road by the Rockwool gate.

Jennifer King, who owns a business located nearby and whose father’s best friend is buried at the cemetery, filed a police report when she saw a gas company contractor back his pick-up truck into the cemetery and over grave sites to turn around. Mountaineer Gas put up a fence along the edge of the road shortly afterwards. King notes that to put up the fence, Mountaineer Gas trespassed on the cemetery after receiving the attorney’s warning.

Family Roots

“I’m going to start crying in a minute,” Shelley Murphy said, as she walked among her ancestors with reverence. “You’re walking on a grave right there,” she admonished, as a relative walking with her stepped near the plot of the Goens family headstone.

A genealogist, Murphy seemed to be familiar with every name inscribed on the headstones or tiny plastic or metal markers. All the names belonged to families related in some way by birth or marriage. William Goens (1861-1919) and his wife Harriet (1865-1927) were the children of slaves, Murphy said. Ann Goens, buried nearby, was her second great-grandmother.

Murphy knows many of their stories. One ancestor, for example, took 1,000 seeds from the apple orchard by the cemetery—the one bought by Rockwool–with her when her family went to homestead in Nebraska.

In an open letter to Governor Jim Justice, Murphy said her “heart was broken” and described the construction equipment as an “invasion” disturbing those who had been resting in peace. She said she is angry that no effort was made to contact descendants or trustees and no public hearings held.

Monique Crippen-Hopkins said it was hard to explain how she felt about the pipeline construction near the graves of her ancestors. “I’ve got a whole bunch of emotions going on right now,” she said. “I feel like they already struggled so much in life. Just let ’em rest, let ’em rest.”

A Question of Historical Significance

An official designation of historical significance by the State Historical Preservation Office would assist in efforts to protect the cemetery.

Local historian Jim Surkamp traces the pre-Civil War ownership of the land to Susan P. Dandridge, who, records show, owned 64 enslaved persons. The cemetery, Surkamp believes, could have been the place where slaves were buried.

But, in 2005, an archeological study was conducted which concluded that the cemetery does not have historical significance, according to criteria established by the State Historical Preservation Office. The public cannot read and assess the study in full, however, because it is redacted to “protect artifacts.”

Soldiers of the Black Army

Veterans from four wars are buried in Boyd Carter Cemetery—both World Wars, Korea and Vietnam. Military history has not recognized the importance of the contributions of black soldiers. Prior to the Vietnam War, they were segregated into separate units.

Joyceann Gray, a descendant who visited the cemetery, served in the U.S. military, and her father fought in WWII. Her grandfather lost his life in WWI. She is angry about the threat that pipeline construction poses, especially to the veterans buried there.

“How can you disrespect them? This is just unconscionable,” she said. “We’ve got to do something about that.”

Murphy, Gray and others are calling for the cemetery to be protected from incursion and appealed to Governor Jim Justice. His office, calling the cemetery’s preservation “very important,” asked the Department of Culture, Arts and History to review the matter.

Time may be running out, though. Efforts so far have not deterred Mountaineer Gas. Workers are trenching to lay pipe on the Rockwool site, and the work is getting close to the cemetery. It could encroach on it any day now.

George M. McDowell, West Virginia, Private First Class, 369th Infantry, World War II

Beneath a thicket underneath the shade of an elm tree lies a knocked-over tombstone, its face nearly covered by black and grey moss, the resting place of PFC George M. McDowell.

Beneath a thicket underneath the shade of an elm tree lies a knocked-over tombstone, its face nearly covered by black and grey moss, the resting place of PFC George M. McDowell.

McDowell was born in 1915, died in 1949 at 34 years of age. Like many youth of his generation he answered a call to join the armed forces after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941. The U.S. Army was segregated at that time. McDowell served into what later became known as the “Black Army.”

Separate from the units of white soldiers, many of the Black Army units saw little or no combat. Most Black Army units worked in support of combat units, building roads, culverts and bridges or transporting cargo. They provided the hands and labor to load and unload supplies and ammunition onto ships and trucks, driving the cargo to where it was needed, and performed maintenance of vehicles.

McDowell, however, went with the 369th Infantry into combat during World War II. He fought in New Guinea and later went to the Bismarck Archipelago, Philippines. Private First Class McDowell would have been an infantryman and learned the combat skills he needed to survive hand-to-hand battle against the Japanese when he fought them on the Bismarck Archipelago. He would have learned combat skills at Fort Leonard Wood which included hand-to-hand fighting with a bayonet, marksmanship skills with the M-1 rifle, and close order drill skills.

Herbert Hoover Ross, West Virginia, CS3, U.S. Navy

Nearby is the grave of another veteran, Herbert Hoover Ross, West Virginia, CS3, U.S. Navy, who served as a 2nd Class Commissaryman Cook. He helped prepare the meals on the galley at his unit. Days for him on the mess deck would start long before the sun rose and ended long after the day was done. Three meals to prepare daily, and mouths were always hungry. He also served two years in the Army Air Corps before the Air Force came into existence. He died in 1956.

His nephew Brian Ross, born two decades after he died, has been keeping up with the grounds of Boyd Carter cemetery since the 1970s as best as he could. He lives nearby and said it was his only way to pay tribute to the family that preceded him. He is concerned about the possibility that some graves are unmarked, and Mountaineer Gas is trying to lay a pipeline next to it without knowing where they are.

“Back in the 70s, there were plates and markers that we couldn’t make out the names, but we set them up and tried to keep up the cemetery,” he said. Ross said he has mowed and trimmed the weeds back, but there are some sections where trees and vines have grown over the graves. And there are more metal plates and name markers but weather and time have removed their identities.

Ross provided a photograph of his uncle, “Herbie” as he calls him, when he was in the Navy, with his mother, Estella I. Ross, who is interred nearby.

Private John Ferguson, World War I

Private Ferguson was born in 1895 and was 22 years old when “the war to end all wars” began. He lived until 1995. His wife Alice and his son Edward, another veteran who served during the Korean War, are laid to rest next to him.

James Alfred Jackson, West Virginia, Private First Class, 93rd Engineers, World War II

PFC Jackson’s gravestone, stands out, although it is worn from 71 seasons of harsh weather. Jackson was born in 1922 and died in 1948, just a few years after the war ended.

Jackson was deployed with the 93rd Engineers to Canada to build the Alaska-Canada Highway. It was an important strategic route because the War Department viewed the Japanese threat against the Aleilutian Islands as a danger to Alaska and needed a land route built rapidly to transport military armaments to defend Alaska. They sent the 93rd Engineers to the Yukon Territory and the ALCON Highway was completed in 18 months. They worked without days off.

Jackson would have been decorated with the American Campaign and the World War II Victory Medal. He earned the Good Conduct Medal for his excellent service during the War. He died two years after the war ended in Scranton, Pa., but was buried near his hometown in Jefferson County.

Private Edgar J Goens, 4222nd Quartermaster Car Company, WWII

Private Goens was deployed to Leeds, Great Britain, and helped drive cargo supplies to the ships that were involved in the D-Day invasion on June 6, 1944. The 4222nd Quatermaster Car Company, like other Black Army units, was kept apart from the units of white soldiers. Edgar J. Goens was the son of William and Harriet Goens, also buried there.